What does ‘thinking outside of the box’ actually mean?

The 9 Dot Problem

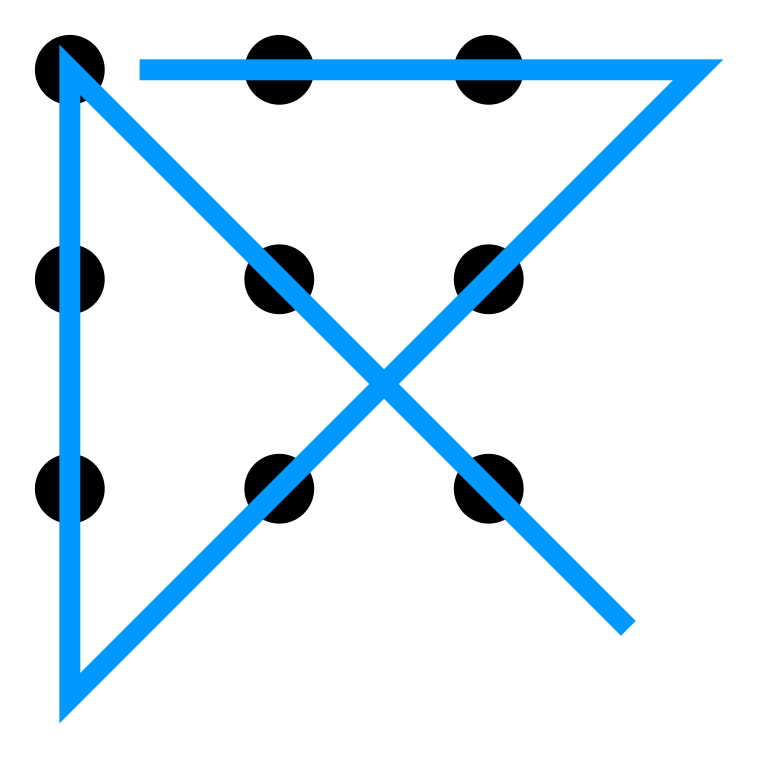

The instruction to 'think outside the box' is usually an invitation to think creatively. It is used as an encouragement to disruptive innovation. It is often linked to the 9 Dot Problem, first published in Sam Loyd's 1914 Cyclopedia of Puzzles. The problem is stated as follows: join all the dots, using 4 straight lines through the centre of the dots, without lifting your pencil from the paper. The solution requires breaking out of the frame created by the dot pattern. But, more importantly, it requires breaking free of an unconscious assumption that most of us have learned in childhood game-playing. Join-the-dots games draw outline shapes of objects from a collection of dots. Such games don't allow you to turn a corner unless it is done on a dot. Solving the 9 Dot Problem requires you to break that rule.

Here is the solution:

Duncker’s Candle Problem

Another well-worn example - from 1945 - is Duncker's Candle Problem. Duncker gave his subjects a set of objects, including a candle, a book of matches and a box of thumbtacks (A). He asks them to show how can you attach the candle to the wall and light it but ensure that no wax drips on the table below. The solution (B) required that the subjects make use of the box containing the thumbtacks as part of the structure, attaching it to the wall as a platform for the candle, and thus catching any wax drops.

What is important about these examples is what is called the Einstellung Effect. Einstellung literally means "setting" or "installation" as well as a person's "attitude" in German. The problem solver approaches a new problem with a framework which is familiar from previous experience. We are constrained by established patterns. It has often been said of military leaders, for example, that they are guilty of 'fighting the previous war'. So thinking outside the box requires us to become aware of patterns and assumptions that are no longer appropriate.

How to avoid the Einstellung Effect in order the 'think outside the box':

Break the rules: find out what rules you are following and challenge them. Once when working with scientists from ice cream manufacture, bakers and cream liqueur distillation, we wondered what we all had in common. It was emulsion technology: the art of suspending fats in solution. But all were following rigidly controlled process manuals that were called the Golden Rules. The creative outlet for these scientists was in finding what they called the 'work-arounds': ways to bend those rules. That was where the ideas flowed freely.

Invite a diverse range of problem solvers: deep domain experts can be combined with viewpoints from other domains. Consider age, gender, education etc. It's ok to have 30 years' experience as an expert as long as it isn't a matter of having one year's experience repeated over 30 years.

Encourage the 'beginner's eye': invite close observation of the problem and encourage questions, including some that may seem foolish. Leonardo da Vinci referred to this as 'Saper Vedere', 'learn how to see'. Leo Esaki, a recent Japanese winner of the Nobel Prize, advises us never to lose our childhood curiosity.